The Misreporting of Manslaughter in Man of Steel (2013)

Suicide By Superman

This is an important distinction for one reason: the phenomenon is one also faced by real, human police officers. In recent times, many police departments have publicly been called out for questionable practices and controversial public incidents involving use of deadly force. But the phenomenon I’m discussing, “Suicide by Cop,” is a very real one at the furthest end of the spectrum from questionable or inappropriate response. Specifically, the phenomenon refers to a perpetrator who wants to die, but for whatever reason will not end their own life. By taking advantage of police training and scripted response in use of deadly force, the person trying to commit “Suicide by Cop”will then threaten a cop or hostage to incite a fatal gunshot wound.

2022 UPDATE – In the years since 2017 when I first wrote this article, we have witnessed so much injustice and death as the result of police intervention, and so much of it with clear racial bias in the United States of America. The proliferation of recording technology in the phones we now all carry and on police recording devices has allowed us to witness the horrible deaths of victims we should never forget: George Floyd, Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor, Elijah McClain, so many more. For sympathetic white people who didn’t already see and feel this effect in their own daily life for years, the raised consciousness spurred by the Black Lives Matter movement in response this plague of racial violence has shaken our basic faith in the heroism of law enforcement. In retrospect, that makes the comparison of the Death of Zod in Man of Steel to a “Suicide by Cop” scenario—and the following passage’s reliance on self-reported statistics from the L.A. County Sheriff’s Department and various Law Enforcement publications—clearly unfortunate. I’m not willing to pretend that this horrible standoff of self-destruction and forced traumatic homicide doesn’t even exist, but whatever the real numbers and stories are to the deaths that have been reported as “Suicide by Cop” it’s clear that Hollywood’s fascination with the phenomenon has passed as the reputation of law enforcement itself becomes increasingly tarnished. At the very last, we can exonerate Man of Steel from any unfortunate racial implications so frequent in the U.S (and Los Angeles) when someone dies as a result of law enforcement intervention.

Suicide.org maintains a page on the phenomenon, and from their editorial viewpoint the phenomenon has to be looked at as any other form of suicide before the fact: a sign of mental illness or distress that should be addressed by seeking help immediately. They do, however, note some other interesting facts in some (outdated) statistics, that could use updated numbers and further study:

Suicide by cop occurs more frequently than most people would imagine. In a study that was published in the Annals of Emergency Medicine, researchers analyzed data from the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.

The researchers concluded that suicide by cop was surprisingly common and the number of incidents was rising.

Researchers studied data from 1987 through 1997 and found that 11 percent of officer-involved shootings were suicide by cop incidents.

For a different viewpoint, closer to the perspective of Superman, who was essentially deputized by the U.S. Military in this confrontation, you would need to view “Suicide by Cop” from the perspective of police officers in what is abbreviated as an “SbC” situation. Fortunately a commercial site hosting information and resources for police officers also hosts a page on the phenomenon, as well as an article by Scott Buhrmaster: Suicide By Cop: 15 Warning Signs That You Might Be Involved.

Sadly, reading the views of the phenomenon from the perspective of police officers who face actual deadly threat in the line of duty, it becomes clear how trained and how tactical their mindset must remain to try and find the best resolution to an SbC scenario:

In situations like this, tactical vigilance is critical. Your recognition of the fact that a subject is interested only in having you shoot him should NOT cause you to hesitate to do so if at any point you feel your life is threatened. Remember, this subject wants to die and he may stop at nothing to reach his goal, including taking you or a fellow officer with him.

In [his] book, Dr. Perrou explores two interesting dynamics that he has seen develop in the scores of suicidal situations he has dealt with.

More specifically, it is exactly our cinematic notions of heroism, of breaking with procedure and accomplishing the impossible and saving the person who doesn’t want to be saved, that can present the greatest threat in this law enforcement situation. Mr Buhrmaster writes:

The first dynamic can best be described as “Rescue Dynamic,” [is] a subtle but dangerous phenomenon that can threaten your life. This dynamic is fueled by the fact that most officers are not specifically prepared to face suicide by cop situations. When most officers find themselves face-to-face with a subject who wants to die, the officer’s primary objective can have a tendency to shift from personal safety to subject preservation.

In a suicidal situation, a subject’s death may be inaccurately perceived by the confronting officer as a failure that reflects that officer’s inability to “do his job” which, at that time, he perceived as keeping the subject alive at any cost. In an effort to avoid this “failure,” officers may take such tactically unsound steps as hesitating to fire when a weapon is pointed at him, coming too close to the subject in an effort to create an emotional bond, or making risky “last ditch efforts” to disarm the subject.

Remember that although a peaceful resolution is certainly the desired outcome, it MUST NOT come at the expense of your safety.

In fact, it is our other cinematic notion of heroism when it comes to rescuing a suicidal individual, which can also be the dangerous to the situation: the idea of “talking them down from the edge.” Burhmaster goes on to further describe aspects of the SbC scenario as probed by Dr. Barry Perrou in his book “Suicide By Cop: Inducing Officers To Shoot:”

The second dynamic Dr. Perrou describes in the book could be termed “The Annoyance Factor.” In observing scores of SbC situations, Dr. Perrou has determined that in some cases, an officer’s earnest attempts to help may in fact be perceived by the suicidal subject as an annoyance strong enough to actually expedite the suicide.

Dr. Perrou writes that in instances where a “connection” between the suicidal subject and the intervening officer is lacking, the subject may see death as his only escape from the agitating voice of the officer. Sadly, the officer, seeing that his efforts to resolve the situation peacefully are not being effective, tries even harder … which only compounds the subject’s interest in escape.

The Suicide by Cop phenomenon can manifest when someone who has no intention of hurting a police officer or bystander, but wants to die, tricks an officer into responding with deadly force. It can also take place in violent and criminal situations in which a perpetrator would rather die than be taken and imprisoned. It is an extremely volatile situation, where deadly force on the part of the suspect is at least threatened. When it comes to Zod, not only is actual deadly threat very much established, but he can never be disarmed. It is not known if he could even be apprehended, or held anywhere on Earth against his will.

As we near the conclusion of Man of Steel, most of the rogue Kryptonians were sent into the Phantom Zone with the successful execution of the U.S. Military portion of the two-pronged attack. Superman, in fact, returns… just in time to down Zod’s attacking colony ship and ensure the military team uses the phantom drive aboard baby Kal-El’s original escape vessel as a one-shot weapon to bomb the Kryptonian ship and baddies back to the Zone Age.

One could argue that the Phantom Zone itself is just a comic-book metaphor for a death sentence, made palatable and clean (and about as permanent as actual death in your average comic-book story). Some of the outraged write-ups of the final act of Man of Steel, such as Darren Franich’s article for Entertainment Weekly: ‘Man of Steel’ ending: What the New Superman Movie Gets Wrong, seem to apply a selective attention and application of comic reference to place even more damage at the feet of Superman:

“What actually happens is that Superman opens up a black hole in the middle of a major American city, which is clearly not a stupid thing to do,” Franich opines. Not only did the military endorse and enact the plan he is referring to, but to most comic-book fans, the Phantom Zone refers to Kryptonian prison. Despite the word “singularity” thrown around in good measure, if we’d seen a black hole opened up over Metropolis it would have been the last thing we’d have seen in the movie.

After the Kryptonians and their ship is sent back to the Phantom Zone (through the… urp… ahem… singularity… ugh), only Zod is left, with no convenient way to follow the original plot idea and ban him, too, to the Phantom Zone—as discussed in an Empire magazine podcast with David Goyer, summarized in this article on Indiewire: Christopher Nolan Initially Disagreed With The Ending Of ‘Man Of Steel,’ ‘Superman: Birthright’ Writer Hates The Result.

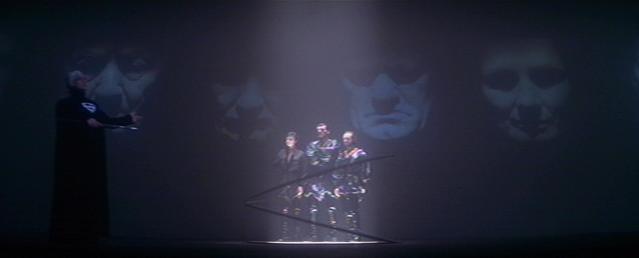

It is with these meaningful words that Zod begins his final attack on Superman and Metropolis:

“I exist only to protect Krypton. That is the sole purpose for which I was born, and every action I take, no matter how violent or how cruel, is for the greater good of my people. And now, I have no people…”

Zod continues to represent his clear and present threat to everyone around, “I’m going to make them suffer, Kal. These humans you’ve adopted, I will take them all from you one by one.”

We expect a lot from a cinematic Superman, particularly if we’re fans of his various comic interpretations over the years. After the release of Batman V. Superman last year, Russ Fischer of BirthMoviesDeath directed disgruntled viewers to cleanse their palette in his article ALL-STAR SUPERMAN Is The Antidote to Zack Snyder’s Scowling Alien, while also admitting “I’m not a Superman lifer.”

Those of us who are Superman lifers, and as old as I am, will remember the Silver Age and its planet-towing, New Power of The Month™, taste-the-rainbow Kryptonite shenanigans. There was good and bad both to be found in the period. Grant Morrison did indeed capture all that was best and fun about that era in his limited series All-Star Superman—complete with cosmic anvils and our hero’s fantastic super-intelligence—and DC Animated did a great adaptation of that title as well. But Fischer ignores that cinematic Superman has really already taken unfortunate cues from Silver Age camp and absurdity: the aforementioned Kryptonite continent lifting from Superman Returns; taste-the-rainbow Kryptonite shenanigans in Superman III; New Power of The Movie™ in Superman II (remember throwing the giant cellophane S from his chest?); even turning back time itself by reversing the planet’s rotation in Superman.

It was time for cinema Superman to face the consequences of his choices, especially on his very first call to action, without turning back the clock and taking them back.

Zod details Kal’s chances during the battle, as he masters his own power of flight, “I was bred to be a warrior, Kal. Trained my entire life to master my senses. Where did you train? ON A FARM?”

In the late 1970’s, when you opened a Superman comic, you already knew, without a doubt, that nothing in the story could possibly really harm Superman. The fantastical science fiction, superhero and reality-bending insanity stories that played out in those old low-quality light-grey pages survived on variety and inventiveness, more than willing suspension of belief. Comics and soap operas all share common characteristics of the “long-term serial,” namely: impermanent death creates unkillable heroes and villains, and thus increasingly outlandish and unbelievable stories.

Perhaps I’m being disingenuous about The Silver Age of Superman, a bit, but Fischer and others are themselves being unfair in comparing a new origin story with a completely non-camp, realistic, “modern day” tone… with an unabashedly outlandish story of a wizened Superman, respected and accomplished, wrapping up his concerns at the precipice of his final Christ-like sacrifice. These critics and fans wanted Superman to figure out “something else” to stop Zod. But the truth of this story, this retelling of Superman’s origin story, is that Superman doesn’t even know if he can do anything to stop Zod.

This winds up being the police equivalent of expecting a rookie cop on his first patrol to handle one of the most complex crisis negotiation situations a police officer can face, a hostage and suicide by cop scenario, without training and without warning.

Clark Kent: “Don’t do this! Stop! Don’t!”

General Zod: “Never!”

The final scene with General Zod and Kal-El/Clark Kent above becomes the moment of crisis negotiation, and its timing is key. Zod’s rampage up until this point has been directed entirely at defeating Superman, and it had reached a stalemate. Zod’s tactics now switch to force the choice, to force Superman to kill him. His heat vision, directed by his gaze, has no reason to take its time and let the threat against the family linger… if he really wanted to kill those people, he would look at them instantly and they would die, on with the rampage. His only reason to delay—to make the threat verbal—is to be killed, to kill himself by Superman’s hand. Given seconds to decide, Superman is forced to use his most immediate and lethal means to stop Zod and save those people.

It’s a heart-wrenching scene, for different reasons, for different viewers. It has to be, to depict its subject matter accurately and with fairness to the law enforcement officers who have endured the experience. Certainly I’ve quoted critics and comics purists who may have confused their disagreement with the story’s direction with their disagreement with Superman’s decision. Waid details this response for him:

Superman wins by killing Zod. By snapping his neck. And as this moment was building, as Zod was out of control and Superman was (for the first time since the fishing boat 90 minutes ago) struggling to actually save innocent victims instead of casually catching them in mid-plummet, some crazy guy in front of us was muttering “Don’t do it…don’t do it…DON’T DO IT…” and then Superman snapped Zod’s neck and that guy stood up and said in a very loud voice, “THAT’S IT, YOU LOST ME, I’M OUT,” and his girlfriend had to literally pull him back into his seat and keep him from walking out and that crazy guy was me. That crazy guy was me, and I barely even remember doing that, I had to be told afterward that I’d done that, that’s how caught up in betrayal I felt. And after the neck-snapping, even though I stuck it out, I didn’t give a damn about the rest of the movie.

As the credits rolled, I told myself I was upset because Superman doesn’t kill. Full-stop, Superman doesn’t kill. But sitting there, I broke it down some more in my head because I sensed there was more to it since Superman clearly regretted killing Zod. I had to grant that the filmmakers at least went way out of their way to put Superman in a position suggesting (but hardly conclusively proving) he had no choice (and I did love Superman’s immediate-aftermath reaction to what he’d done). I granted that they’d at least tried to present Superman with an impossible choice and, on a purely rational level, and if this had been a movie about a guy named Ultraguy, I might even have bought what he did.

Waid goes on to backfill his response to that moment with circular-but-sound logic that Superman hasn’t earned it, because of aforementioned and agreed-upon stance that we didn’t see Superman saving enough citizens of Metropolis. This criticism of the story is so widespread and reported across the internet (and by extension distorted), that it often comes across as a condemnation of the character’s action—and a false implication that Superman had a choice at that moment other than killing Zod or letting those people die.

Saying “Superman wins by killing Zod,” Waid misses the truth of that final moment: Superman doesn’t win at all. Superman is Zod’s final victim, traumatized by being forced to be Zod’s weapon of suicide. Surrounded by rubble and death, nobody has won. Is it too uncomfortable to face that, in a more realistic story,—one that tries a bit harder to mirror actual life—this is the actual truthful outcome of unleashing living weapons, good or evil, in violent confrontation?

Another blogger, J. R. LeMar, perhaps mixes objection to story direction with objection to story decision more directly in his post SUPERMAN DOES NOT KILL. EVER. NOT UNDER ANY CIRCUMSTANCES. NO MATTER WHAT “CONTEXT.”

That still doesn’t make it okay, because the whole point of Superman is his belief that there is always a better way. And Superman, with all of his powers, will find some other way. Plus, the context defense only works if he were real, and these events were really happening to him. But this is all fiction. The writers of this film specifically created the situation and the context in order to justify this action, as if it was out of their hands. They chose to write a story where Superman’s “only option” was to kill someone. They should not have done that.

The judgment against Superman and his “hero failure,” which we in fact have seen to be very much a liability in a legitimately dangerous Suicide by Cop situation, mixes seemlessly with anger at the writers for concocting a scenario for the character that “only works if he were real.” I thought that was the point, and the benefit, of a live action adaptation in the first place. What’s worse, judging Superman’s action under the weight of comic-fan story expectations sends an unfair message to the law enforcement officers forced to take a life in the line of duty.

As mentioned before, police action has come under increased scrutiny, lately, and public trust of law enforcement has been shaken by a number of tragic deaths, accusations of racial profiling, and riots in protest. Indeed, Josh Voorhees questions the very application of the SbC terminology in his article for Slate, The Problem With “Suicide by Cop.” It’s beyond the scope of this article to discuss misapplication of the term or its effects on society, but the clear deadly threat and suicidal intent Zod displays at the end of Man of Steel qualifies the scene for the term. Certainly someone has already thought to add the example to TVtropes.org article on Suicide by Cop.

The larger societal question about the term’s application is worth asking, just as the cinematic story of a new hero victimized into confronting a lot of grey areas before he was ready is a story worth exploring. Superman is traumatized by what he was forced to do, and it is to Voorhees credit that he notes the trauma seasoned police officers face when they are forced to kill:

To be clear, police officers do sometimes have little choice but to use lethal force. And we should have tremendous sympathy for those who are put in that horrible situation: Research suggests that those officers who take a life in the line of duty are more likely to suffer PTSD-like symptoms and to retire early from the force.

Do heroes kill? In the end, that becomes a very personal question, it seems, one on which there is not a lot of consensus. If you rule it out completely, you rule out heroism in police officers, in soliders… roles we hope to revere and look up to, if we feel they are being applied fairly, rightly. Do comic-book heroes kill? They are almost by definition hero roles outside the bounds of the law, but again, you will not find a very clear answer about killing across the breadth of everything available, from The Punisher to The Bat-Man.

You can’t even really get a clear answer from comics history, despite Waid’s strong beliefs, as to whether or not Superman kills. Man of Steel perhaps unsurprisingly takes this element (among others) from the controversial 1986-1988 John Byrne turn relaunching the character in the series titled Man of Steel, as ComicBook.com notes in Russ Burlingame’s article Man of Steel: Five Things The Movie Took From John Byrne’s Superman.

Byrne’s take on the character was the subject of a lot of pre-internet controversy, and you can review polarized viewpoints in the blog ComicsCube.com’s Why I Can’t Stand John Byrne’s Superman: Man of Steel contrasted with Last of The Famous International Fanboy’s Why I love John Byrne’s Superman: Man of Steel. So it was perhaps inevitable that its eponymous cinema interpretation, by exploring similar themes with its Superman, would find itself awash in the same controversy.

Now that some time has passed, some have looked upon the movie a bit more kindly, particularly now that its follow-up has been released and received even harsher critical appraisal and dissection. Burlingame follow-up his previous article for ComicBook.com with the 2015 revelation that Superman Legend Dan Jurgens: [Finds] Man of Steel Handled Zod’s Death Better Than The Comics, preferring the aftertaste of Snyder’s depiction of Suicide by Cop more fitting the character than Byrne’s depiction of judge, jury, and executioner.

Man of Steel, Movie of Kleenex

Making controversial choices and forcing a cinematic tradition that had become increasingly self-referential and disconnected to return to reality, Man of Steel had a lot of work to do to in addition to launching a new extended cinematic universe. Marvel was already several movies into their “Stage One” plan when Man of Steel was released in 2013, and audiences had a lot more “samples” of those heroes to individually reject or enjoy in order to arrive at an overall level of satisfaction, and come together to buy record amounts of tickets for The Avengers. Executives at Warner Bros., I speculate, have demonstrated less patience when it comes to approaching Avengers-level box office returns.

The film that was released ironically disturbed some cinema purists even as it improved on their complaints about the previous films. It paradoxically provoked some Marvel fans into attacking it even as it presented them with an different alternative to how their hero movies handled the subject matter. Man of Steel even tapped into a renewed long-standing acrimony and controversy within the DC and Superman purist fan-base, in a way that was very much inspired by places the DC comic series itself had dared to explore thirty years before.

It wasn’t perfect, but it did please me greatly. And leave me thinking about who Superman really was and whom he should aspire to be.

With the weight of an entire cinematic universe and the projections of stratospheric revenue for its studio behind it—and the expectations of so many people pulling it in so many directions with so many desires—the movie retained its unique identity and forged a new path like Byrne’s series did before it. Before its follow-up, I had hopes Snyder’s work like Byrne’s would be eventually remembered fondly if controversially, and followed by further brave choices on the part of Warner Bros. Studios. I had hoped the flood of internet commentary would be endured bravely, and the story direction would remain true to our reality.

In the opening of Batman V Superman: Dawn of Justice, we see the destruction of Metropolis from the viewpoint of Bruce Wayne, a selective perception of destruction omitting much of the world-engine damage and coincidentally glimpsing mostly the Zod battle damage. I was intrigued to see Snyder capture some of the critics of Man of Steel’s judgement and response in the character of Bat-Man in its follow-up. As Marvel continues to voyage faithfully into comic territory that will become more and more outlandish, I had hopes that DC and WB would continue to find that way to take these characters and make them seem real.

Unfortunately by the end of that follow-up, I became even more convinced that executive impatience for that Avengers money is the Kryptonite to the the DC Extended Cinema Super-Universe. In that context, whether you liked the story they chose to tell or not, Man of Steel stands taller, prouder, more heroic.

It’s risky and brave treatment of Superman deserves a great deal more credit than it got.

Advertisement